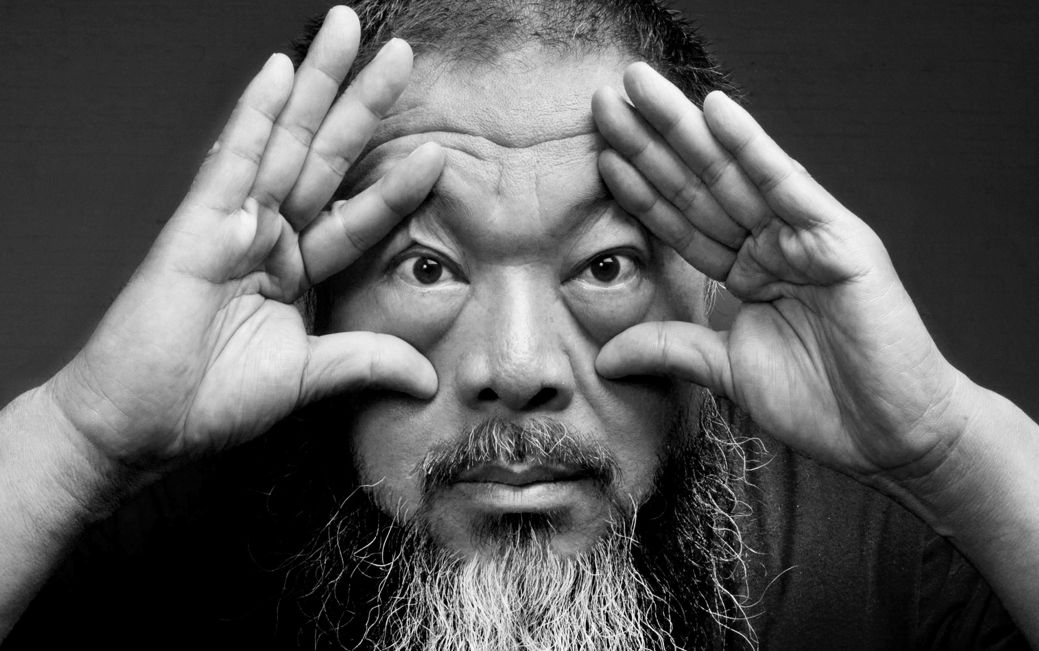

Ai Weiwei on the HK Protest Movement

This story originally appeared in Hong Kong Free Press

Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei made his name in visual arts, film and architecture, before his critical commentary against the Chinese government led to persecution and a trial on allegations of tax evasion. Ai moved to Berlin in 2015, and has become an outspoken advocate for migrants’ rights. During the height of the anti-extradition law protests in Hong Kong, HKFP spoke to the influential artist about his work, human rights and China under Xi Jinping.

HKFP: Let’s begin with the human rights crisis in Xinjiang – where thousands of Uighurs have been detained. How should the world react?

Ai Weiwei: The human rights crisis in Xinjiang is no different from any other human rights crisis. It could be occurring in the United States, Europe, Myanmar, Yemen, or elsewhere. China says it has its own model, one that follows “Chinese characteristics.” We must recognise human rights as universal. Any attempt to separate human rights issues through differentiating by region, culture or policy is merely a distraction. China’s assertion of “Chinese characteristics” is simply a cynical attempt at crushing human rights. What is happening today in Xinjiang has elements reminiscent of what happened during World War II, both to the Jewish people in Europe, as well as to the Japanese Americans in the United States.

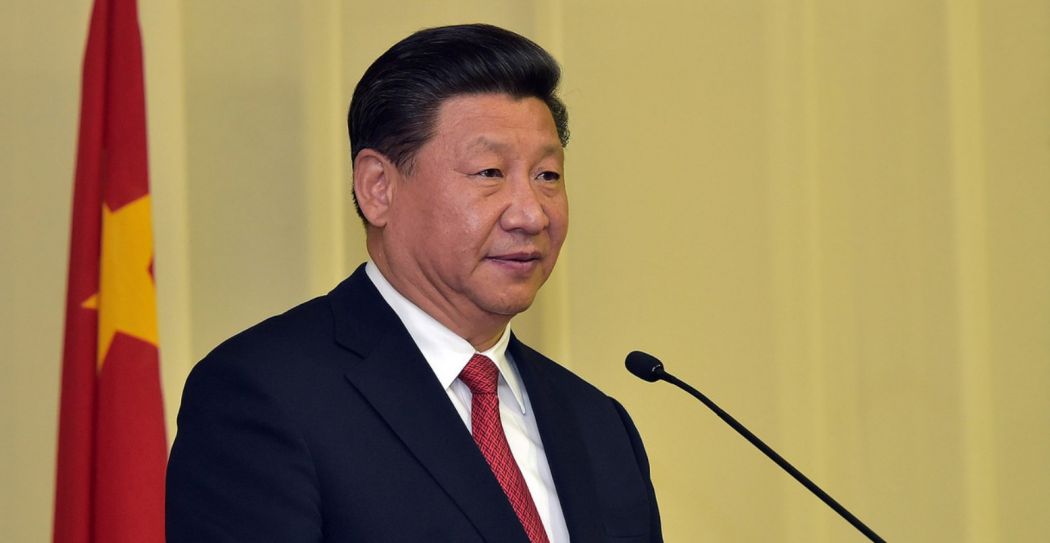

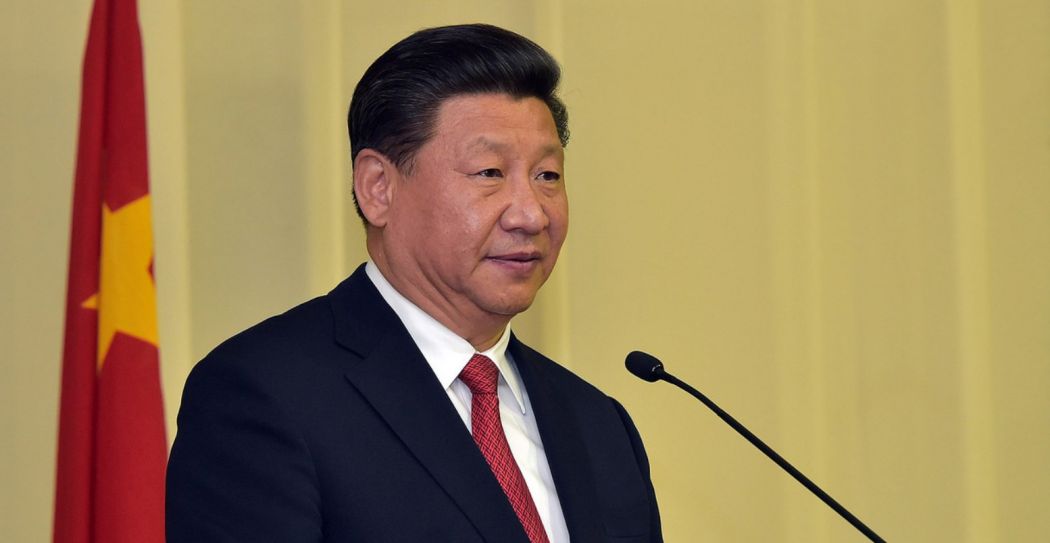

Chinese dissidents often say that China is becoming more totalitarian under Xi Jinping. What do you think of Xi’s rule? Is it delicate, or will it continue until he dies?

China’s policy has not changed since the Chinese Communist Party established the nation in 1949. Sometimes it becomes more extreme, while at other times there may be some space for tolerance. Whether Chinese policy is extreme or tolerant is a reflection of the Party’s own condition. If the condition is one of fragility or urgency, policy and methods of control will become more extreme.

China is like an overgrown baby which has not yet been equipped with knowledge or rationality. Its judgement is often incomprehensible. China is also a nation which can maintain this kind of condition for a hundred years. The only possibility that China’s competitors have to stop it from becoming a threat is to recognise it as such and to safeguard a future for a civilised society.

The way in which China has achieved its rapid growth is clearly in conflict with so-called Western values—the human rights that have been established over the past 100 years which have brought us to the present moment, and from which China has also benefited greatly. However, China does not recognise the established norms, preferring instead to maintain barbaric methods of governing and control, presenting a danger to the whole world.

You usually live in Germany. What is your impression of the country after it accepted Liu Xia and two political asylum seekers from Hong Kong?

Generally speaking, Germany has a policy which may be a good example for other European nations. It has accepted many dissidents, including myself, Liu Xia, and the two Hong Kong political asylum seekers. Germany accommodates 1.2 million refugees. German policy appears firmer on these issues. However, Germany as a part of Europe and of the so-called Western world has forged the strongest relationship with China. The German chancellor has visited China a dozen times. China sees Germany as a strategic partner. German industry leaders have openly stated that the future of Germany is in China.

Still, what Germany has done on human rights issues is little compared to what needs to be done. Many European nations have sidelined human rights for short-sighted economic gain. This will be a continuing trend and there is no clear way out because we live in a capitalist society. After the Cold War, globalisation became the new social value. Unrestrained capitalism was exported as a new form of colonialism. Today, business interests are sexier than upholding essential values. This is not just a European problem but afflicts the United States as well.

What is the meaning of your work on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ 70th anniversary? What does the footprint design represent, and how do you hope to spread the message?

Human rights need to be discussed in every textbook, as part of every school curriculum and should inform state policy. Failing this, we will inevitably see humanitarian crises intensify. Today, over 70 million refugees have been forced from their homes. Many regional conflicts are still being waged, many young people are being killed and the rest are deprived of an education. The world is being torn apart and the mainstream media pays scant attention to the actual human cost because they are a reflection of our skewed priorities and values.

This raises the question: what kind of society are we living in? That is why I designed this flag, as a simple reminder of the 70 years in which we have adhered to the concept of shared humanity and to the basic principles of human rights.

The design of the flag was inspired by footprints made in a Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh. While filming a documentary there, we asked some adults and children to leave their footprints for us. The footprint is the most recognizable human mark, existing since the moment humans have been able to stand upright.

In recent years, your work has focused on migration. Where do you consider home to be? Why?

My work has focused on refugees not simply because of the issue of migration, but because these are people who have been abandoned and victimized by society, who have no voice.

I have never considered myself as someone with a home. In 2009, I clearly announced, “Fuck your motherland.” I would only consider a home, or a motherland, as a community of people who share an idea rather than geographic borders.

Moving on to Hong Kong – you’ve hosted several exhibitions here (in 2015 and 2018). In your opinion, how has the city’s art scene changed during that period, particularly in terms of freedom of expression?

I have had some art activity in Hong Kong. It is a society with a special, modern energy. At the same time, I do feel that art in Hong Kong should be much more aggressive or make a more global impact. Hong Kong still benefits from being the most international city in Asia. It has a strongly educated population. The city needs more art that reflects its energy, hope and imagination.

Would you have safety concerns about visiting Hong Kong in the future?

I would. Under “One [Country], two systems,” if the Hong Kong people do not fight to protect their own rights, then they could easily slip into the same bleak conditions faced by Shenzhen or any other Chinese city. Human rights violations would be pervasive and uncontrollable. It would come under the same flawed Chinese judicial system that is subject to the Party’s interests. Once a judicial system loses its independence, anything can happen and no one is safe.

Will any of your future work focus on Hong Kong’s political situation?

I have no plans to make work just for Hong Kong. I write and speak about the issue and am completely in support of Hong Kong’s human rights defenders. My work comes naturally. Even though I don’t have any plans, something could happen at any time.

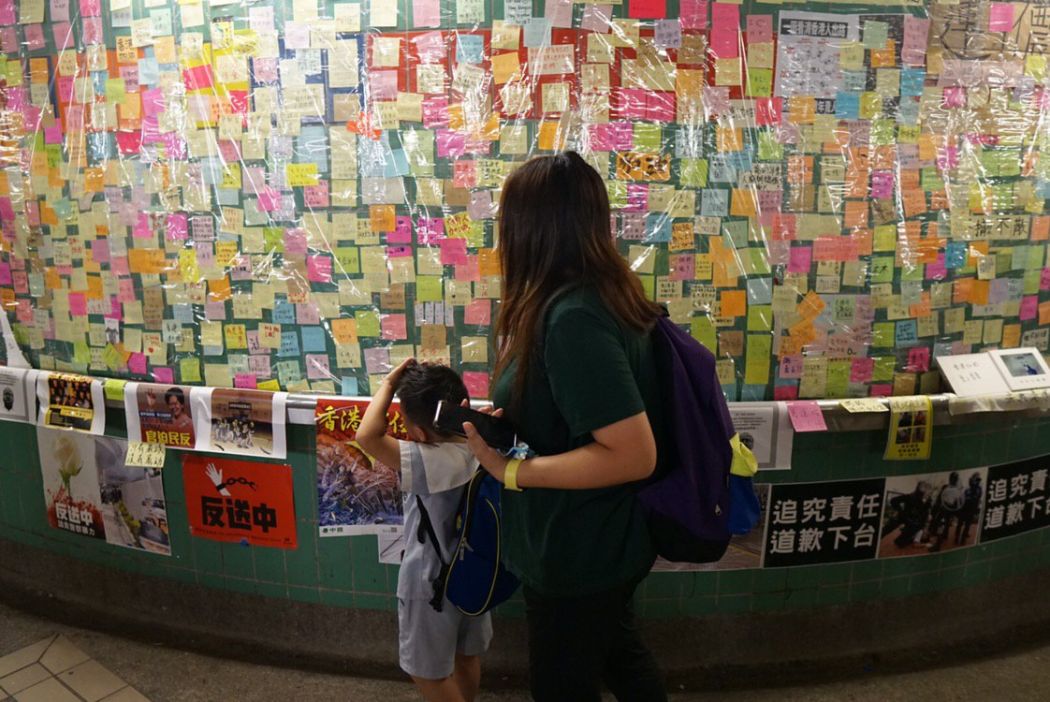

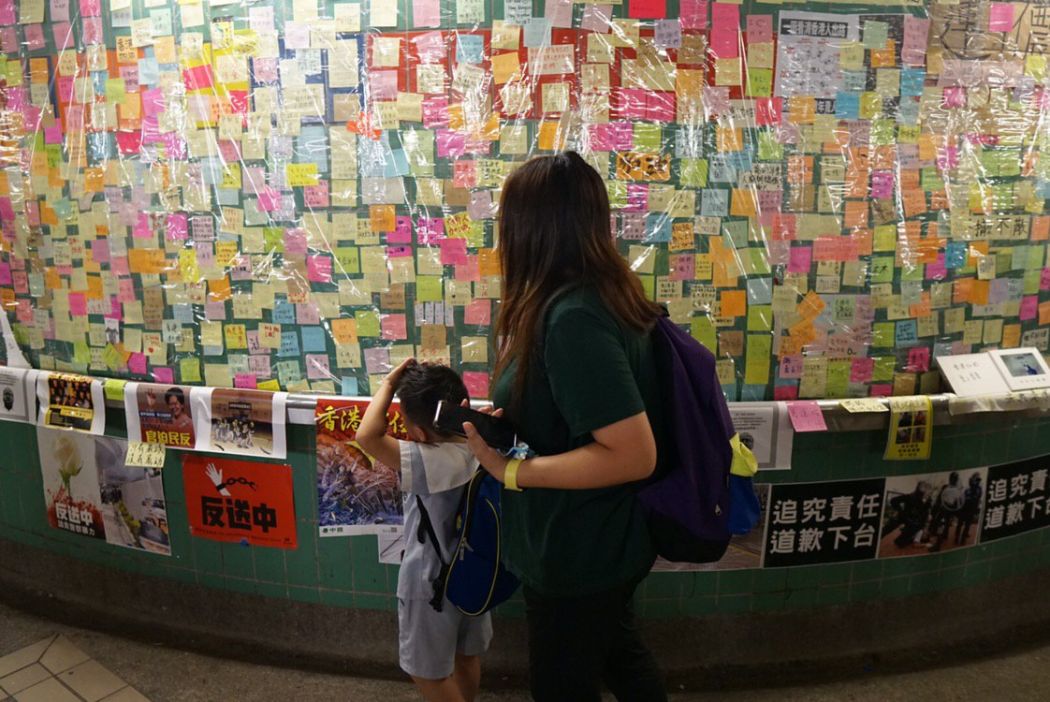

You called Hong Kong’s anti-extradition demonstrations “the most beautiful protest in the world.” Why do you think so? And do you foresee a greater crackdown from Beijing on the horizon?

My impression of Hong Kong comes from an earlier time. After I was released from secret detention in 2011, I realised that the Hong Kong people had made a great effort in support of my release. There were many demonstrations and young artists who placed posters with my picture and name all over the city. There was even a projection of my portrait and name on the facade of the People’s Liberation Army Garrison building. Those were acts by individuals. I never knew who they were and they never tried to get in contact with me. I was deeply touched by these actions.

Just knowing that my values were shared by another person reminded me that humanity still existed even in the most extreme conditions. That is one of the reasons why I fully support those young people who are expressing themselves now. They have nothing to hide. Why should they hide their voices? If they did not have their voice, how could they survive? I think everyone can make their own judgement, especially young people in Hong Kong. They are clever and brave. Some have said that Hong Kong people are very practical. Yes, and human rights are very practical. It is about everything we care about. Every night, we have the same dream: to live as free human beings, rather than to live under a dictatorship or the violence of authoritarianism.

This is why I believe the Hong Kong demonstrations are the most beautiful. They are so peaceful, rational, and those taking part are so young. It is very different from most demonstrations elsewhere. Those are usually oriented around a shared political agenda. But the people marching in the streets of Hong Kong are there for freedom. It is abstract, but at the same time it relates to everyone and it definitely relates to the values I treasure most.

I have said in the past that I am a Hongkonger. Today, I reiterate that. I am a Hongkonger. I admire them and feel deeply sad when I see four young people have already lost their lives in this fight. They clearly stated what the fight in Hong Kong is about, that freedom is as valuable as life itself and they were willing to sacrifice their own lives to prove it. Nothing could be more beautiful.

China faces a massive problem if the youth of Hong Kong continues to protest. It is a challenge that alarms the rest of the world as to what kind of society China is. If they don’t stop the protests, the democratic voice will get louder and there will be better conditions for freedom. But how can they stop them? Hong Kong is not just another Chinese city. If that were the case, the military would have moved in and crushed it immediately. There would not be any media coverage or international attention. This already happens all the time in China. Hong Kong is different. It still has its recent history as a British colony, reflected in its adherence to the rule of law, its independent judiciary, and relatively wide range of political freedoms.

Meanwhile, the UK has shown no vision or will to uphold its most important values and we see the deterioration of those values globally. The UK’s failure gives us stronger reasons for supporting democracy and human rights in Hong Kong.

You were targeted by the Chinese authorities over tax issues – do you think that, similarly, Beijing would use the extradition law broadly in order to stifle dissent?

In an authoritarian society, the clearing away of obstacles and enemies is a deeply rooted principle of survival. There is no way it will forget or forgive anyone that raises the question of its legitimacy. You can’t negotiate with tigers about the colour of their skin.

Hong Kong’s extradition protests have given artists a space to create art: protesters decorating walls using post-it notes, painters working on-site, protesters drawing umbrellas by wiping dirt off tunnel walls. Why do you think people are drawn to creating art during times of crisis?

Freedom of expression is the most important weapon to combat authoritarianism. Authoritarians simply have no imagination, and without that, they have no future. Often, we see protesters also lacking in imagination, but Hong Kong’s protests have demonstrated a capacity for adaptation. They are learning from the fight. There is no other way to attain this education than to be in the thick of it.

There will be bloodshed, as we witnessed last week with the organised attack by the mob in white. The enemy is vicious and will take any means necessary to crush the movement. So demonstrators need to have not only mental clarity but also a defined strategy. They must explicitly announce their ideas and mobilize people, but also have clear tactics to unmask their opponent’s vulnerabilities. That is the art of the dissident and a whole generation of young people will learn from this because they have a formidable opponent.