Can Hong Kong's Mass Protests Lead to Masterpieces?

This story originally appeared in Artnet

‘The Greatest Art Is Going to Be Produced in Hong Kong’: Amid Raging Protests, Some See an Opportunity for the City’s Art Scene

by Vivienne Chow

When the black-clad young protesters in helmets and masks broke the glass doors of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council Complex on the night of July 1 and stormed the building, an artwork by Lam Tung Pang accidentally became a part of one of the most defining moments in the city’s history to date. Hanging in a conference room in the headquarters, the large-scale, multi-panel painting Centuries of Hong Kong presented Lam’s artistic interpretation of the city’s transformation from a serene fishing village to a cosmopolitan, skyscraper-crowded metropolis over 150 years.

That trajectory is now set to change course. Hong Kong is facing unprecedented political turmoil, posing burning questions about the former British colony’s future and its identity under Chinese sovereignty. The massive demonstrations against the controversial extradition bill that have raged since the beginning of June show that many Hongkongers, particularly the younger generation, are yearning for something beyond the material comforts that meet their basic day-to-day needs. The core values of freedom, democracy, and the rule of law—ideologies that contradict China’s repressive regime—are what they identify with in their aspiration to build a true version of the colorful cosmopolis depicted in Lam’s painting.

The outcome of the fight for Hong Kong’s liberty will have a profound impact on the city’s cultural identity—and its artistic expression as well.

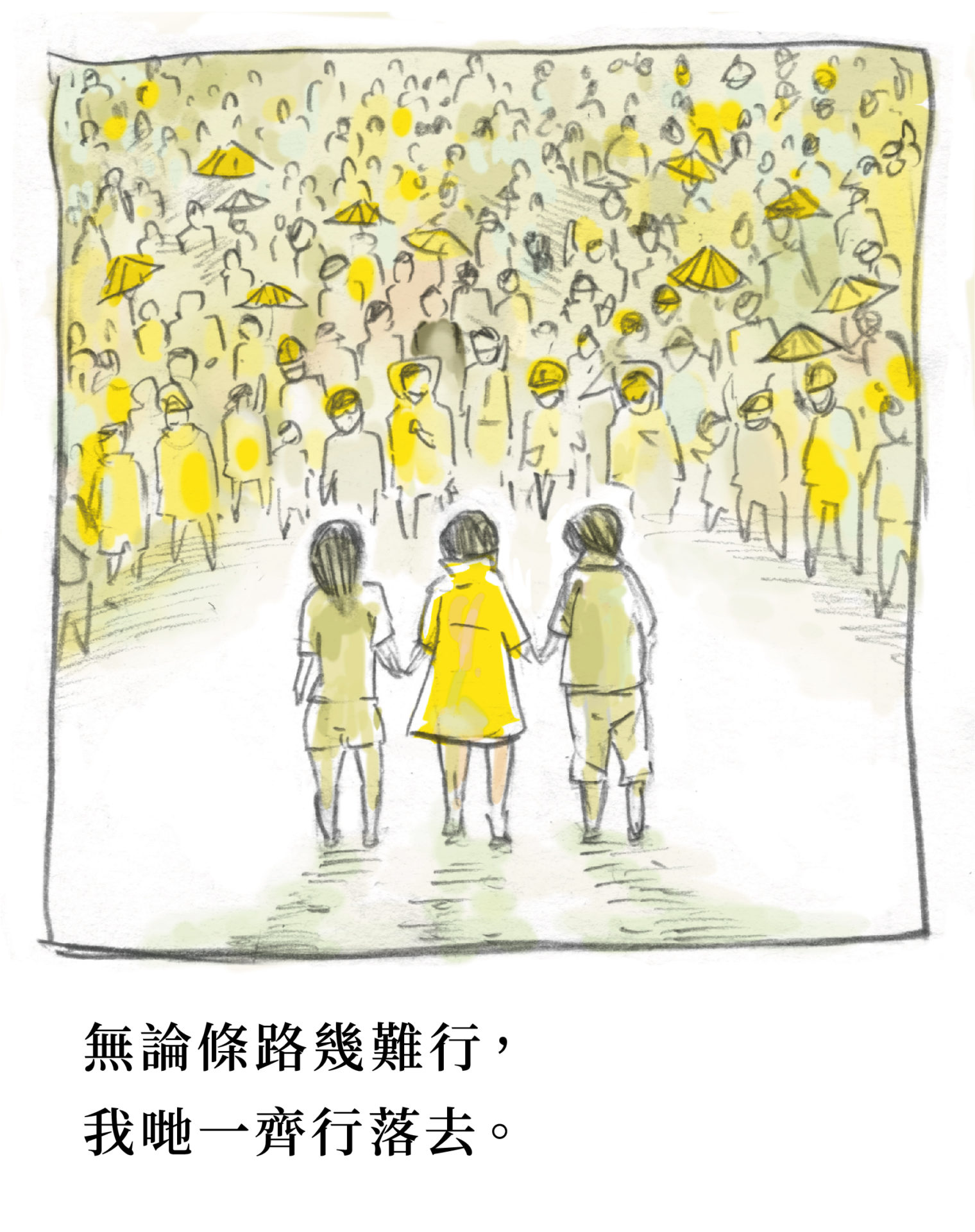

According to Abby Chen, head of contemporary art at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, the recent Hong Kong protests are the most important cultural phenomenon the world has seen over the past decade. The city’s people, she said, have demonstrated creativity at all levels, mobilizing themselves from cyberspace to the streets to safeguard their freedom against those in power.

Chen believes that Hong Kong’s art is likewise poised to enter an age of energetic invention comparable to the 1985 New Wave movement in China. “It’s not just about the geopolitical situation,” she said. “This is about being human, and the kind of resistance and resilience that we are seeing. The world should be aware of it. If they are not, they are missing something that is critically important.”

“The greatest art,” she said, “is going to be produced in Hong Kong,”

“Be Water, My Friend”

Bruce Lee once said, “Be formless, shapeless, like water…. Water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.” The kung fu legend first put Hong Kong on the world map in the 1970s through his movies. Today, the city has taken inspiration from the cinema icon’s philosophy for a political cause that makes international news headlines.

The ongoing protests against the extradition bill, which allows people living or traveling in the city to be extradited to other jurisdictions—including mainland China—to stand trial, are now collectively known as the “Be Water” movement. One lesson learned from the 2014 Umbrella Movement, which called for genuine universal suffrage without Beijing’s interference, is that long-term protests occupying the city can eventually lead to failure when public support dwindles. This time around, the movement has a different strategy.

“This is a post-Umbrella generation, with new blood, new tactics, and new organization—it is much smarter,” said Badiucao, a Chinese dissident artist now living in Australia. His Hong Kong show was abruptly cancelled last year amid pressure from mainland China, and he has now been producing artworks and illustrations for protesters.

Traditional political leaders, from pro-democracy lawmakers to even Joshua Wong, the superstar student leader of the Umbrella protests, can only play a supporting role. The lead actors are the ensemble cast of Hongkongers, who coordinate their strategies in real time through Telegram and the discussion forum LIHKG, especially during standoffs with the police.

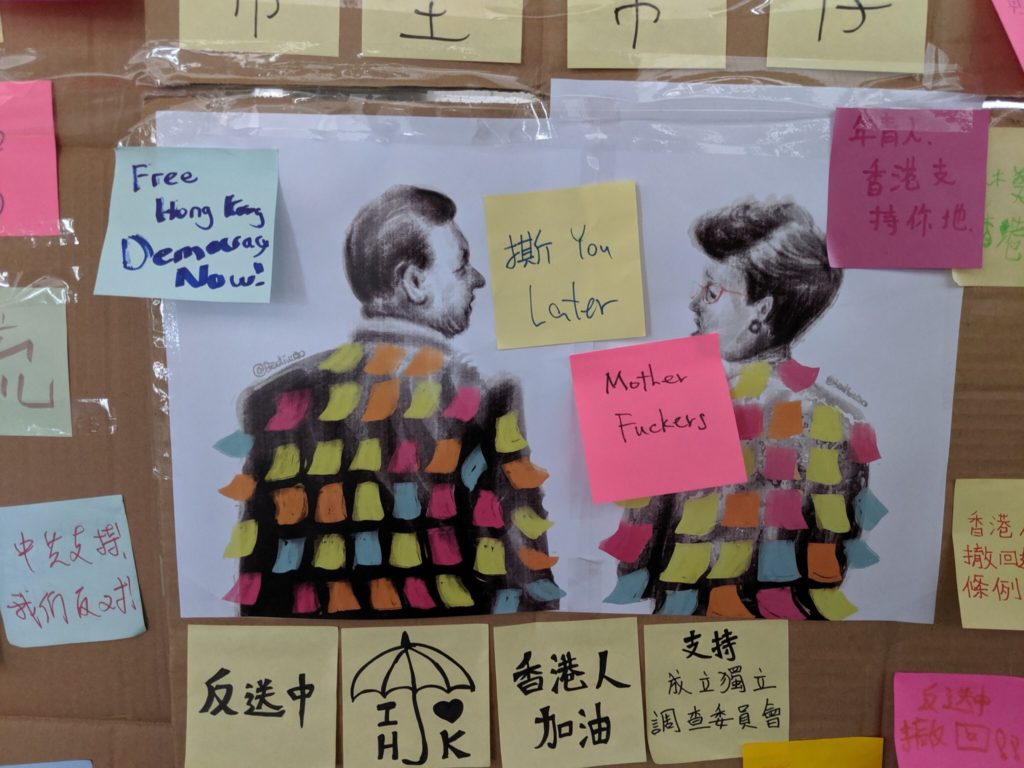

Protests are shapeless and formless, and they come and go like water. Rallies are taking place across the city. Political cartoons, drawings, and illustrations are being widely circulated on social networks. For the first time, people crowdfunded advertising campaigns for the protest movement in major foreign-language media outlets—in English, French, German, and Japanese, for instance—to draw the world’s attention. People are also calling for the boycott of pro-Beijing media, and the advertisers that place ads in these media outlets.

This outreach extends beyond mainstream media as well, with protestors also using online platforms to encourage overseas Hongkongers to stage protests in cities from New York to London and Berlin. And “Lennon walls,” made up of Post-Its on which people write their thoughts, have become a new front for conflict with the pro-establishment camp, with supporters of mainland rule being caught destroying the Post-Its and even violently attacking young people guarding the wall.

The wellspring of creativity on the part of the protesters stems from the fact that they know the establishment continues to reject their voices. While Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam has already suspended the bill, they demand that the government withdraws it entirely and sets up an independent inquiry to look into police violence on June 12. Even though former chief justice Andrew Li and some members of the pro-establishment camp support the idea, Lam refuses to concede. But while distrust in the government and fear of the loss of freedom to Beijing has brought despair among young people—it has already caused four political suicides—the protesters display no sign of backing down.

“We are with the young people,” said Lam Tung Pang. Despite not knowing if his work Centuries of Hong Kong was damaged in the chaotic Legislative Council occupation, he said it was not the most important thing to him—and that he, like many people in the city, understood why young protesters chose an extreme method of expressing themselves. After all, he noted, there is mounting anger and frustration with changes in the city governed by an aging pro-Beijing camp, and the protesters are only asking for what they are promised by China in the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in 1984 and the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

“The changes are not just about the change of a flag,” the artist said. “The impact on you is real. And the result is a reinvigorated identity.”

Hong Kong 3.0

The University of Hong Kong’s Public Opinion Program has been tracking the changing Hong Kong identity since the 1997 handover to China. In its latest and final survey—conducted in the second half of June, after first one million people took to the streets on June 9 and then two million followed on June 16—researchers found that 76 percent of the interviewees identified themselves as Hongkongers, an all-time high since 1997, while those who identify themselves as Chinese constitute an all-time low for the same period.

The artist Leung Chi Wo, whose work often deals with the city’s memories and the fluidity of Hong Kong identity, said the extradition bill has caused immense fear among Hongkongers, who were worried that it could tear down the legal firewall between the city and mainland China and further tighten the city’s freedom of expression as a result. It is the worst political crisis the city has seen since the 1967 leftist riots happened during colonial times, he said.

But, on the bright side, the movement has allowed Hong Kong to redefine its cultural identity, according to Leung.

“In the past, Hong Kong could be defined by language”—Cantonese—”and cultural behavior,” he said. “It was a narrow definition. But these events give us a chance to look at the core values of Hong Kong. It is all about freedom and inclusivity, regardless of your origin or ethnicity—because if the bill passes, everyone will be affected.”

Ironically, Hong Kong should thank its chief executive Carrie Lam for uniting the city’s people in an unprecedented way. “The government keeps saying that the bill will fill the loopholes in the law and stop Hong Kong from being a ‘paradise for fugitives,’” said Leung. “But this is exactly what Hong Kong is: a city that accommodates diversity and people from everywhere.”

The independent curator Angelika Li, who recently launched an ongoing curatorial project about the city’s changing identity called “Homeland in Transit” in Basel, Switzerland, said Hong Kong has always been a complex and contradictory place. “Artists are questioning who we are, but this moment makes this question even more urgent and profound,” she said.

Hong Kong has long been one of the world’s most important art markets. The city’s own artistic production, however, has yet to enjoy the same renown. The political upheaval might be traumatic, but the city’s battle to hold fast to its freedom and way of life has laid a solid foundation for the future of Hong Kong art, according to Chen, the curator. “Artists in this generation are very lucky in this unfortunate turmoil,” she said.

The explosion of Chinese contemporary art during the 1985 New Wave art movement was a response to China’s major social and political transformation as the country was opening up while at the same time recovering from the psychic wounds of the Cultural Revolution. Chen said Hong Kong artists are now going through something similar—but that, compared to Chinese artists back then, Hong Kong’s artist community already has the tools needed to create a unique artistic language.

“Back then, Chinese artists didn’t have a lot of training that was complete and sophisticated,” she noted. “They were learning and trying.” Hong Kong’s artists, on the other hand, are well trained and grew up in a culturally rich environment, particularly those who were born in the 1970s.

“Hong Kong has the most uninterrupted history, language, and culture from its Chinese side, while at the same time being a British colony for over 100 years,” said Chen. “Artists have benefited from the best of both worlds, receiving wholesome training in both Chinese and Western philosophy and aesthetics. They also have different cultures that groomed them, from music and comics to toys and television. The only thing they did not have was a social turmoil.” And while no citizen would elect to have their freedoms threatened, Chinese artists will now inevitably be shaped by the exigencies of a climactic political moment in “a way that they didn’t even dream of when they first became artists,” she said.

Lam Tung Pang, who worked with Chen for his solo exhibition “Saan Dung Gei” at Hong Kong’s Blindspot Gallery in March, said artists of previous generations dealt with the changing identity of Hong Kong during the handover, but those emotions did not last long, and anyway they lacked the opportunity and context to express themselves. Now, for the first time, he felt that art could really become part of society.

Hong Kong has long been one of the world’s most important art markets. The city’s own artistic production, however, has yet to enjoy the same renown. The political upheaval might be traumatic, but the city’s battle to hold fast to its freedom and way of life has laid a solid foundation for the future of Hong Kong art, according to Chen, the curator. “Artists in this generation are very lucky in this unfortunate turmoil,” she said.

The explosion of Chinese contemporary art during the 1985 New Wave art movement was a response to China’s major social and political transformation as the country was opening up while at the same time recovering from the psychic wounds of the Cultural Revolution. Chen said Hong Kong artists are now going through something similar—but that, compared to Chinese artists back then, Hong Kong’s artist community already has the tools needed to create a unique artistic language.

“Back then, Chinese artists didn’t have a lot of training that was complete and sophisticated,” she noted. “They were learning and trying.” Hong Kong’s artists, on the other hand, are well trained and grew up in a culturally rich environment, particularly those who were born in the 1970s.

“Hong Kong has the most uninterrupted history, language, and culture from its Chinese side, while at the same time being a British colony for over 100 years,” said Chen. “Artists have benefited from the best of both worlds, receiving wholesome training in both Chinese and Western philosophy and aesthetics. They also have different cultures that groomed them, from music and comics to toys and television. The only thing they did not have was a social turmoil.” And while no citizen would elect to have their freedoms threatened, Chinese artists will now inevitably be shaped by the exigencies of a climactic political moment in “a way that they didn’t even dream of when they first became artists,” she said.

Lam Tung Pang, who worked with Chen for his solo exhibition “Saan Dung Gei” at Hong Kong’s Blindspot Gallery in March, said artists of previous generations dealt with the changing identity of Hong Kong during the handover, but those emotions did not last long, and anyway they lacked the opportunity and context to express themselves. Now, for the first time, he felt that art could really become part of society.