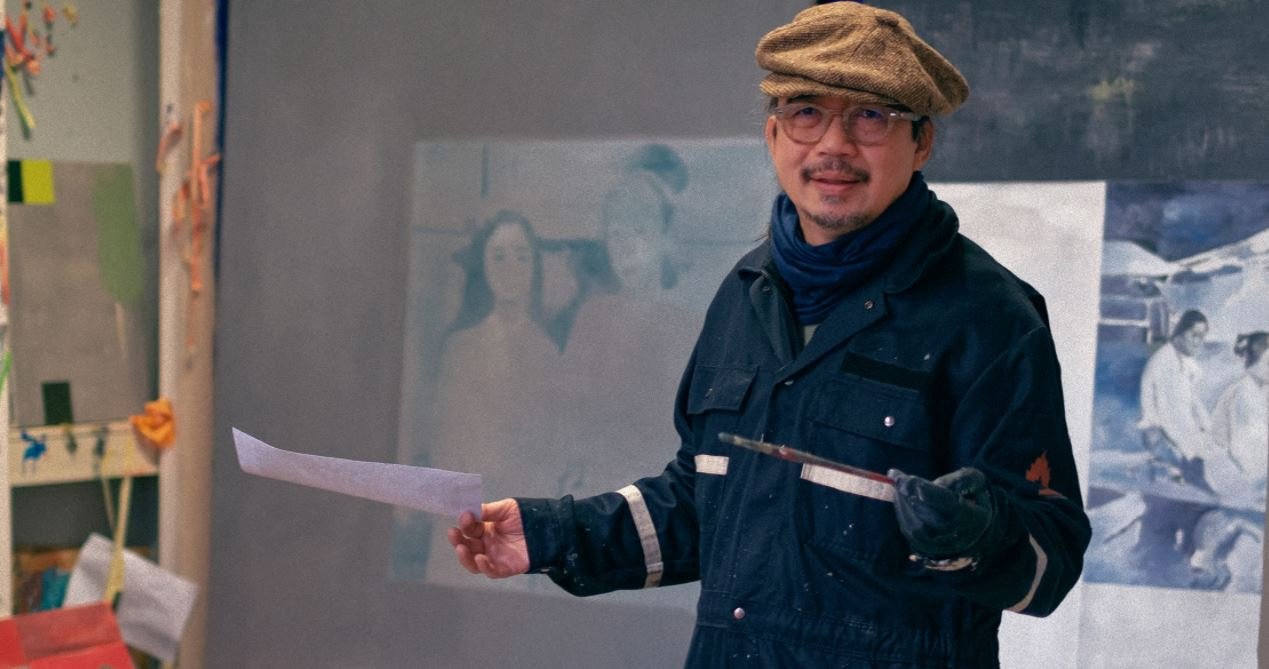

Sawangwongse Ywanghwe: Burma Superstar Making Art in Exile

This story originally appeared in Art Basel Stories.

by Kerstin Winking

‘When I lived in Vancouver, near my home, there was an artist-run gallery called grunt that I passed by every day. Once, I went in and said, "I would like to show here." I was probably 18. The curator said, "Give me a resumé." I went to a café and, for some reason, I wrote one out for him on toilet paper. Then I went back and gave it to him. A year later, I held an exhibition there. The show got some media attention. I thought, "Well, this is pretty cool."

‘I started drawing when I was in elementary school. An older kid drew a manga robot, but I could copy the robot in greater detail. Everyone was like "wow." Each time I made something, the teacher would present it in class, and everybody would be amazed by how realistic it looked.

‘Another layer to my story of becoming an artist relates to my family. After my grandfather’s assassination by the Burmese military dictatorship, my dad fled to the Shan Hills, a mountainous zone bordered by China, Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand. In 1964, he helped establish the Shan State Army, which fought for greater autonomy and democracy for the people of the Shan State. My mother joined him in 1969. After I was born in 1971, we emigrated to Thailand. We were lucky, a few influential Thais helped my family. Because my mom worked, when I came home from school each day, I stayed with an elderly couple living near my home. They would feed me, and I would draw. I learned quickly. When I was 13, my family was granted political asylum in Canada.

‘In Vancouver, like other immigrant kids from Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia, I was encouraged to work from an early age – this helped instill a strong work ethic in me. My mom and I had jobs at McDonald’s, while my dad worked on his PhD in political science at the University of British Columbia. When I was 18, I joined the Royal Canadian Naval Reserve for a year. After that, I received a scholarship and went to study at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. Next, I studied philosophy at Concordia University in Montreal, because I thought I needed it for my art. I took a class called "Existentialism" and another called "Aesthetics." I stopped painting, but I made a lot of drawings. I dropped out after a year. Afterward, I went back to Vancouver and tried to line up some exhibitions, but I was already an outsider. Instead, I took a job in construction. I thought I could do that and skateboard and party. I dyed my hair blond.

‘Then I met Heinrich Nicolaus, who was in Vancouver giving a painting workshop. I was about 25 and completely green. I didn’t attend his workshop but just went to the studio at night and made little paintings. He saw them during the day. On the last day of the workshop, he waited so that he could see me. I told him, "I don’t think I’m a serious artist." He invited me to work in his studio in the village of Montefioralle in Tuscany, Italy.

A few weeks later, I arrived in Florence to a scene out of Hunter S. Thompson’s book, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Wearing a loud Acapulco shirt, Heinrich picked me up in a convertible. He drove us up into the hills of Chianti, passing vineyards and cypresses. For six months, I stayed in Heinrich’s loft and worked in his big studio, which was housed in an old factory. A few years later, we collaborated again in Italy.

‘After my time in Montefioralle, I joined an artist commune in nearby Panzano and we created MoMAP – the Museum of Modern Art Panzano. Basically, it was a house that we rented and used as an open studio. A lot of people came through, and we got an exhibition space in town, which we ran collectively. At MoMAP, I met Max Seidel, the Director of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, and I gave him a copy of my artists book, The Disasters of Military Rule in Burma, which I made between 2004 – 2007. I published the book under my Shan name Huung Hpa, because it was still unsafe for me to use my real name in 2007.

‘In 2004, my father passed away. This was when I started to look at Burma again. I came across my father’s photographs, specifically an image of him speaking into a microphone. I would make small paintings of him, and then I would put the photos away. I made a lot of these small paintings. I think I was working through losing my father.

‘I went to India and Thailand for my book. I had avoided the region for a long time before my dad died. I stayed in Rishikesh, India, and made one or two drawings a day until I had 81 of them. I did little else but yoga and drawing. It was the time of the Saffron Revolution in Burma. My drawings reflected the atrocities committed by the Burmese military dictatorship and referenced Goya’s The Disasters of War, a copy of which I had with me.

‘Looking back, I think my exile was traumatic. Not only my exile in Thailand but the fact that people were getting killed in Chiang Mai. I remember that one of my dad’s comrades, an ex-Shan State Army officer, was assassinated when I was 11 or 12. My way of dealing with it was shutting it all off. Art was my sanctuary.’

Kerstin Winking is a curator and scholar based in Amsterdam. With Dev Benegal, she is the co-director of Painting Exile, a film about Sawangwongse Yawnghwe which will be released in 2022.

Sawangwongse Yawnghwe is represented by TKG⁺, Taipei and Nova Contemporary, Bangkok.

All images by Alex Blanco for Art Basel.